Click on photos to view larger

Every breed of horse is the direct result of the needs and desires of the culture that has created it!

It's with good reason, that the Icelandic Horse is as incredible as he is.

We know that horses and other livestock were brought to Iceland in open Viking boats about 1100 years ago by the first permanent settlers to the island.

The arriving Vikings were a staunch and adventurous group who--despite the obvious difficulties--were enthralled by the freedom, beauty, and wide horizons of their new homes. They were peaceful, family oriented, and resourceful.

A small group of Irish monks had come before them, but because they had no descendants, they did not leave a strong mark on the later culture. I don't know whether they had horses, but it seems almost impossible for them to have survived for any length of time without them.

We also know from DNA testing that the Icelandic Horse is descended from the Mongolian horse.

What I don't know and wonder about is how the Mongolian horse got to Scandinavia and whether the Vikings had a reason to select this special type of horse to bring to their new home or all the horses in the area were like this at the time.

My first thought was that it was Genghis Khan who had brought the future Iceland horses to Scandinavia, but although it was a romantic notion to picture his horde racing full tilt across the steppes, it was an impossible notion. He had not been born yet.

Chances are that Vikings went to Mongolia on their raids and brought horses back with them. Another theory could be that early Mongolian traders traveled as far as Scandinavia and brought their horses. Either way, both the Vikings and the Mongolians were fearless, undaunted, and adventurous.

No matter how it all happened, the horses the Vikings brought to Iceland were an excellent choice--strong, swift, hardy, surefooted, street smart, kind, cooperative, and courageous.

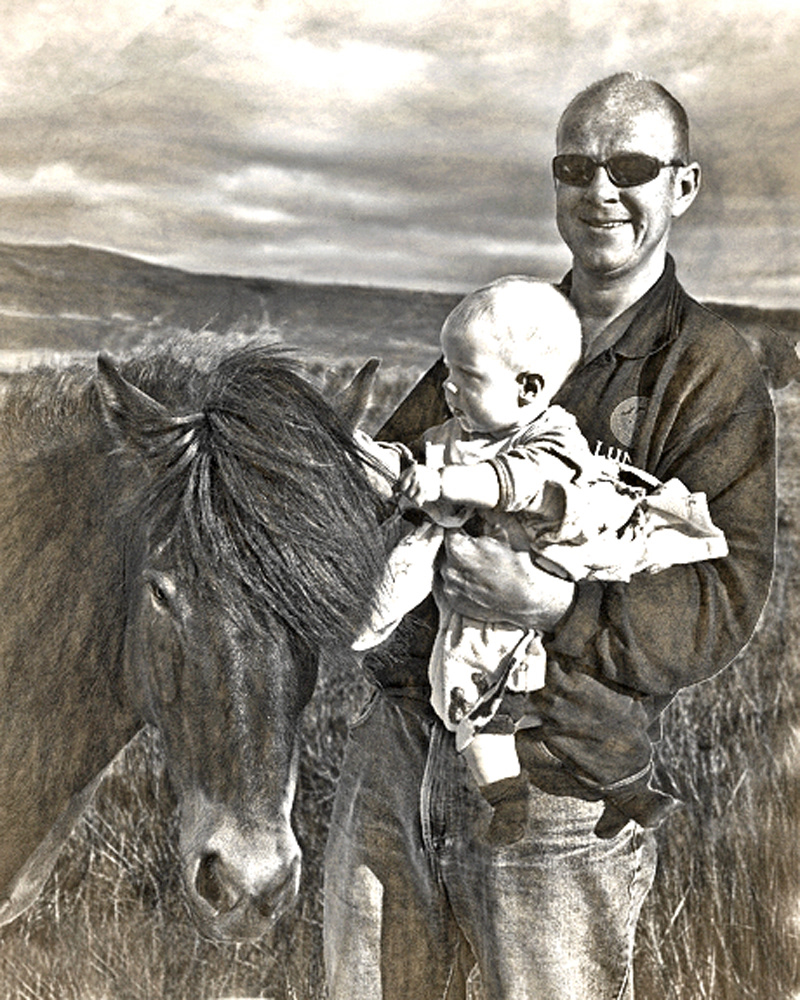

The horse quickly became the mainstay for the new Icelanders--not only as an important means of transportation, but also as a food source. Cows had to be kept inside and fed hay almost all year. Sheep had to be stable during the winter, but the horses had thick insulating coats and could-- provided they were strong enough and had land enough--fend for themselves during even the harshest winters by scraping away the snow and eating the frozen grass underneath it.

Over the following millennium 90% of horses were slaughtered. Perhaps not a memory many horse lovers relish, but undoubtedly the main reason the Icelandic Horse is so incredible, today. Very few breeds have had the luxury of such an extended culling not just by nature but also by man.

Only the strongest, smartest, easiest, and cooperative foals survived to reproduce.

Iceland created a harsh and rugged environment for the farmers and most of the work had to be done during the short summer month. Everything had to be done in an as efficient way as possible.

Because the terrain was too rugged to make roads and have carts, long lines of horses--tied head to tail--were used to distribute the mail, to bring in the hay, to pick up and deliver goods. They were also needed when going to church or traveling to visit neighbors, friends, and far off family.Also, every fall sheep and horses had to be gathered and brought down from the mountains. The excess horses had to be slaughtered and the sheep stabled. As important as it was to have reliable horses, there was little time train them.

Mares were never ridden and stallions were a bother. The solution became for each farmer to every year to--before the rest were slaughtered--select the number of colts he anticipated he would need as riding horses. Knowing his herd, the farmer would look for foals out of mares who had previously produced good riding horses with smarts, strength, endurance, comfortable gaits, and cooperation. Quality foals were also traded between neighbors.

When the colts were two and sometimes three years old, they would be used as breeding stallions. Often neighboring farmers would trade colts for the season in order to limit inbreeding. Once, the reproduction had been set in motion, the colts that had done the breeding would be gelded and turned out with the rest of the herd free to roam and develop until they were five and ready to train. All in all, the method worked very well.

Thingvalla

One of the first things the Icelandic settlers did was to establish the Althing-most likely the first democratic government since ancient Greece. Everyone in the country was expected to show up and camp out at Thingvalla for a combination of law making,court of law judgements, fairs, horse trading,and parties. No one was allowed to leave before all important matters were settled. This was an ingenious way of creating rapid agreement because everyone needed to get back home as quickly as possible to make the most of the short summer months.

One of the most important decrees made by the Althing was to ban the import of all animals. Plagues were harassing Europe and the Icelanders did not want the disease to spread to their island. By then, they had plenty of livestock and doing so would not be a problem. But for practical reasons, they couldn't ban people from coming, especially because more were settlers were still badly needed.

As far as horses go, the ban has never been lifted. And once a horse has set foot on the gangplank of a ship or stepped onto a plane, he is not allowed to return to Iceland. Not only does this guarantee that every Icelandic Horse born in Iceland is has been purebred for a thousand years, but it also prevented contagious horse diseases up until very recently when tourism--horse trekking--became one of the largest businesses in Iceland and visitors began bringing infected riding gear in their luggage.

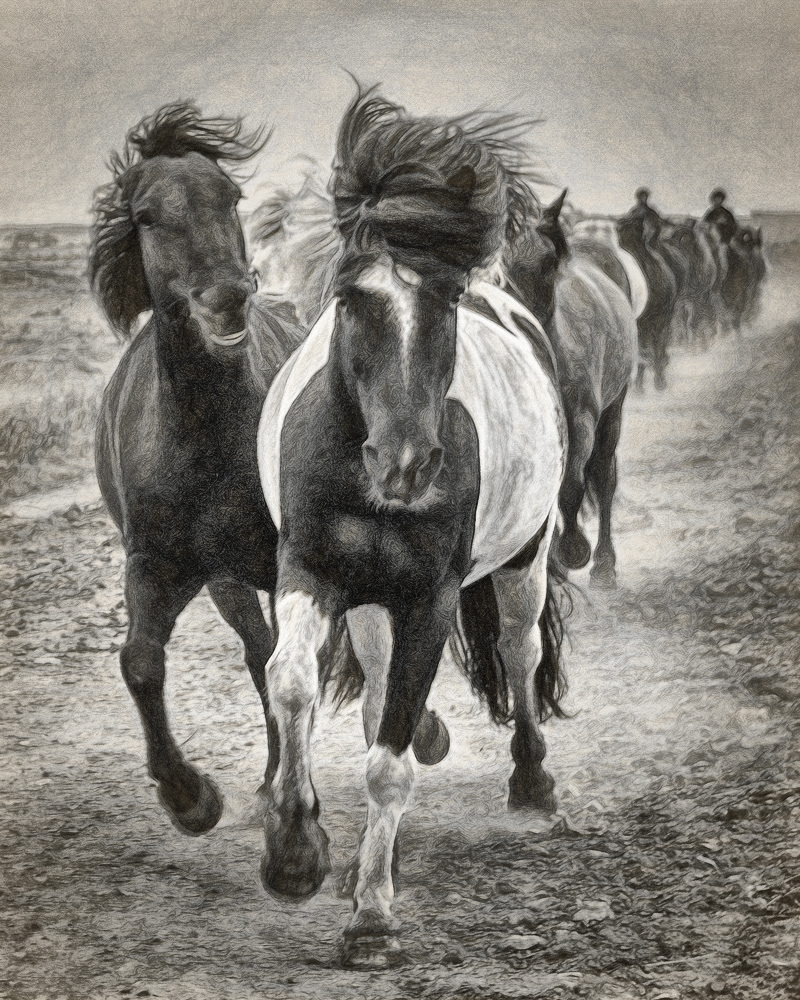

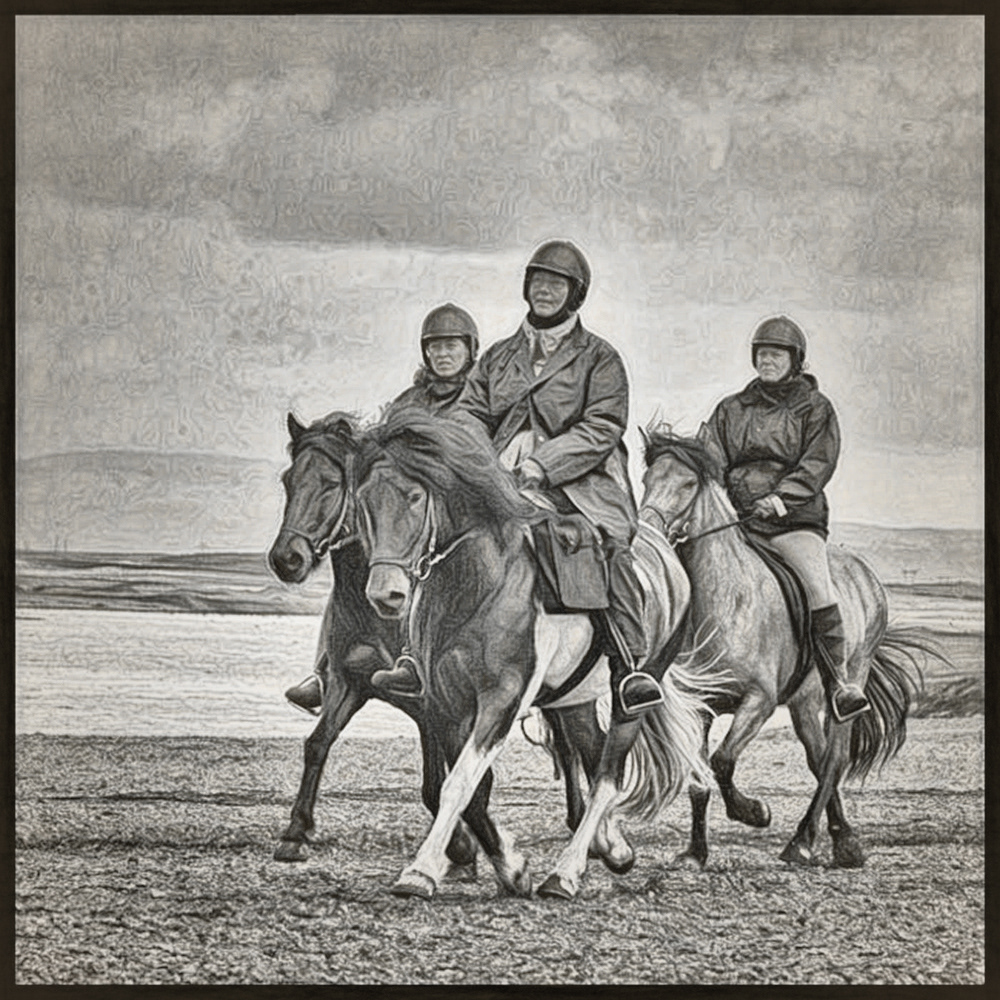

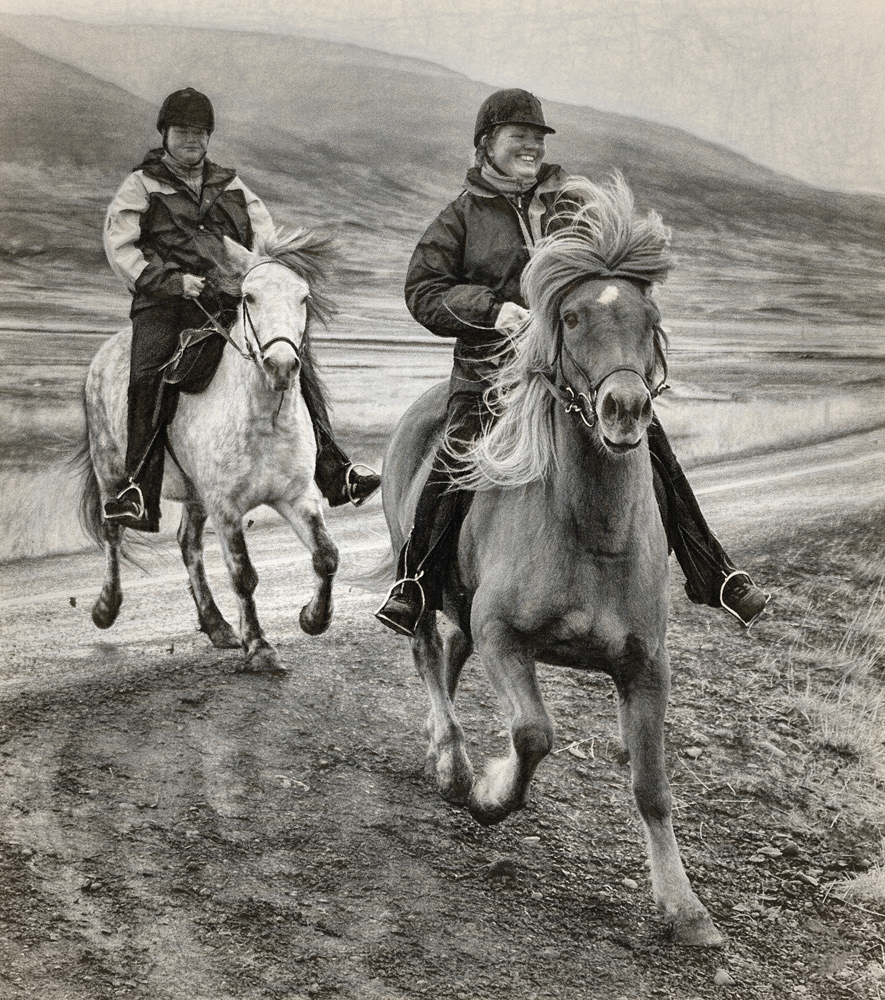

Icelanders are and were a social people. Whenever the circumstances allowed, they would travel across the country to visit friends and relatives. When doing so, they would always ride at a fast clip with a large herd of horses. Along the route, they would change horses every half hour or so--allowing the horses to urinate and graze during the re saddling.

Young horses were brought along to be traded or simply to build up stamina and to learn the ropes of traveling in a herd. Also, young horses would always be hand-horsed (ponied) for at least a year before being ridden. As a result of that and their tractable character there was little muss and fuss when it was finally time for them to be ridden.

The long rides were fast paced mostly in hvalhop,( toelting with the front legs and cantering on the hind). It is the least strenuous gait for the horse and the most comfortable one for the rider. Galloping was only done the last half mile home. By going as fast as possible it was to show that the horses still had plenty of speed and strength left and that was important. Flying pace was strictly a showoff gait, used the last 100 or 200 meters (only on very level ground} before arriving at the church on Sundays and when leaving it.

The horses used to gather the sheep and horses were a special group and were not used for riding at any other times during the year. Because of their arduous work, strength, street smarts and surefootedness was even more important in them than in the other riding horses. As a result less emphasis was put on the comfort of the rider.

Icelandic Horses come in all imaginable colors, but until lately no one really cared what color his horse had. The exceptions were pintos and albinos. They were considered considered ugly and gaudy.

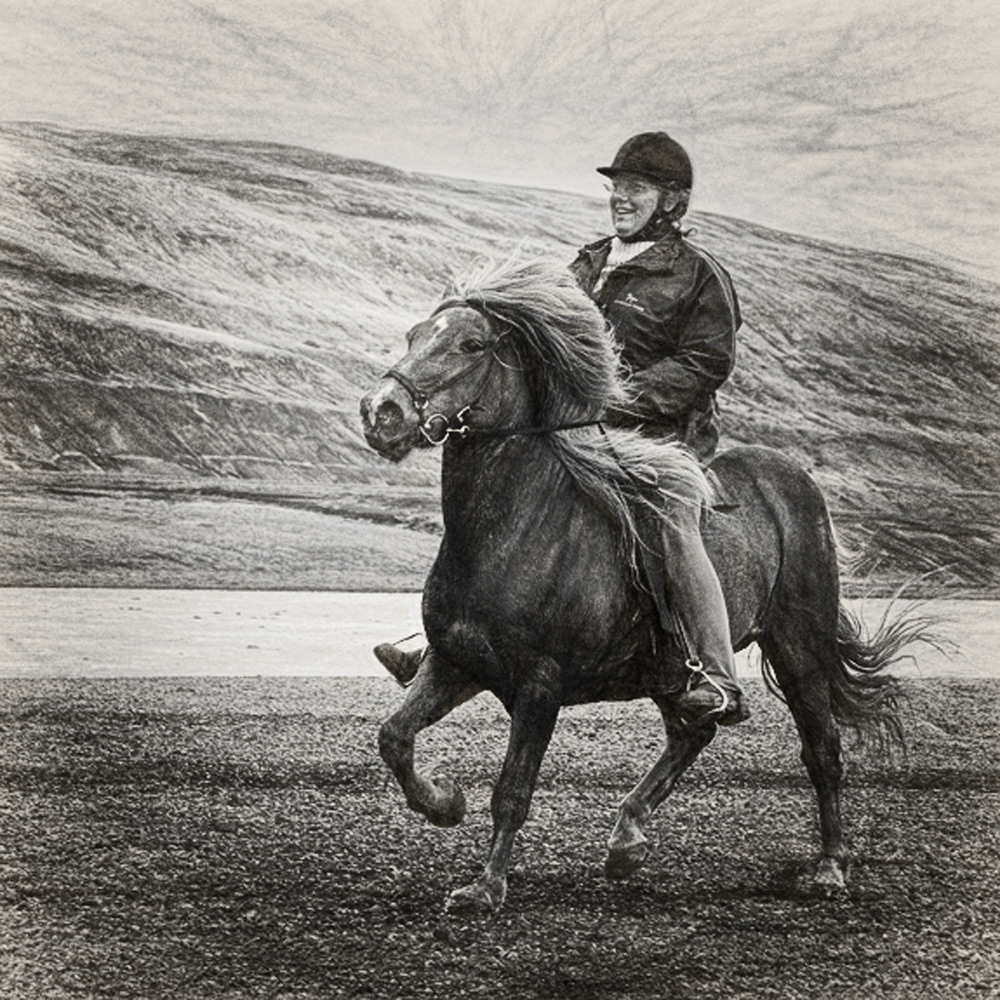

Up until recently, the Icelandic Horse was dubbed a man't horse that could be ridden by women and children. In order to have the strength needed for the long rides across treacherous terrain, they needed to be powerful and fast. Women only rode when traveling and the greatest compliment a riding horse could get was that he was a konur hest: spirited,swift and mighty, yet smooth as glass and gentle as a dove.

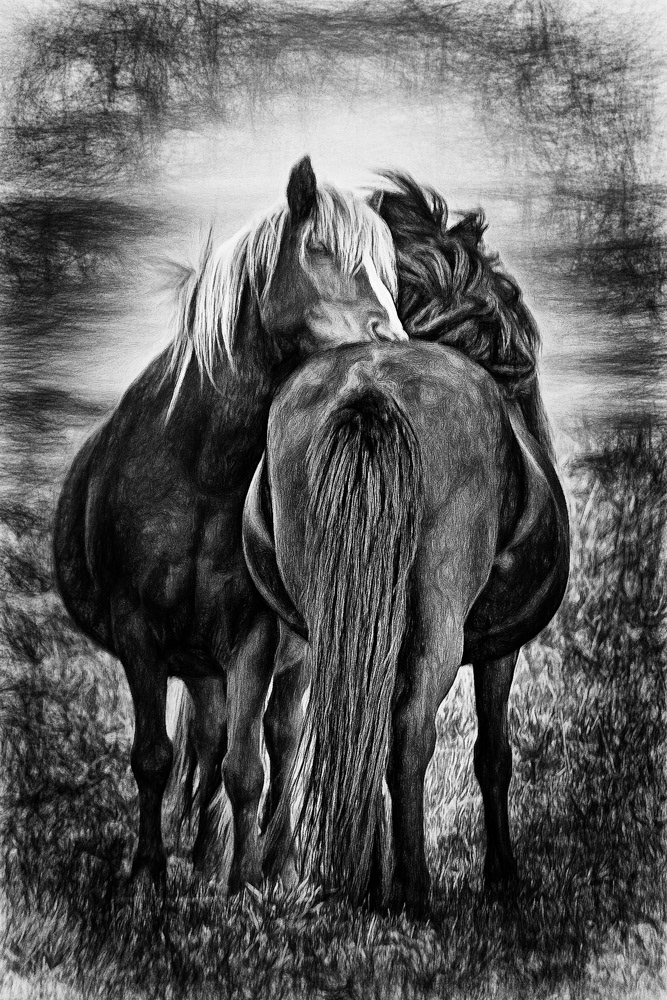

The old stories recounted about the farmers and their favorite riding horses are heart warming.

One told of a man who had become wounded and unconscious. As a result, he fell of his horse into deep snow. Rather than leave his friend and master, the horse lay down giving the man warmth by encircling him until he woke up the following morning and was able to crawl onto his mount. Only then, did the horse get up and carefully carry his rider home.

More general are those tales of the men riding home after spirited gatherings with other men. Highly inebriated, they would have difficulty keeping their balance while riding, but he horse would move under them whenever they were lurching. Once a horse and rider got home, the horse, rather than walk directly to the barn as he was wont. The horse would go to the kitchen door and patiently wait until the woman of the house opened it and helped her husband down. The horse was given a treat for his effort, but nonetheless!

As the centuries went by nothing much changed in the relationships between the horses and their owners. The Icelandic people were staunch, freedom-loving, resourceful, and hardworking. Although they loved to gossip, they were very tolerant of one another and helped each other when the need arose.

As time passed, there were many times of that need--all caused by natural disasters like volcanoes. During and after one of these eruptions almost all of the horses were killed, leaving a very small gene pool to re-surge from.

One thing of interest is that whereas most cultures mount and dismount their horses on the left, Icelanders adopted the more natural way of doing so from the right. The reason for this was that the peaceful Icelanders did not carry swords so did not have to worry about them getting in the way as they were getting on and off their horses.

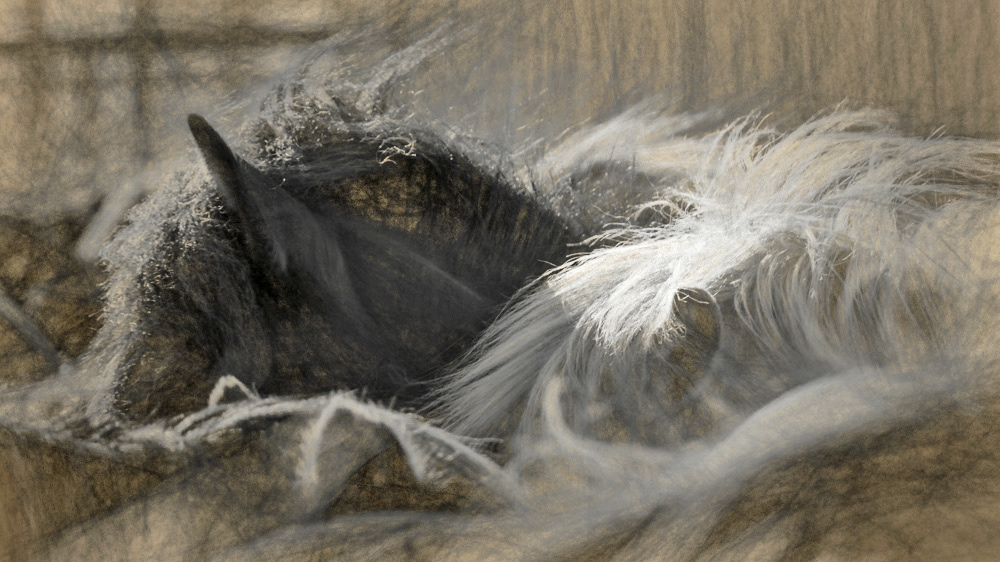

Icelandic Horses have a different fat burning capability, metabolism, and digestive system than other breeds of horses. They can also pant like dogs to get rid of excess heat. It is unclear whether these traits were a part of their Mongolian heritage or they developed them in their new home.

The horses usually cam out of the winter very thin, but immediately started gaining weight as soon as the new grass came up. Towards fall, they would forage constantly packing on the pounds and growing heavy coats in preparation for the winter.

During this weight gaining time, their energy level would lower and they were never ridden except when absolutely necessary.

A few centuries ago, Icelandic horses began being exported as work animals as well as for slaughter. In Great Britain and the United States, he was used in the mines. In Scandinavia, he not only became the poor farmers work horse but was used by the army to pull cannons.

He developed the unfair reputation of being stubborn and difficult. True, he was smart, freedom loving, and strong minded. But there was reason behind it when he hesitated to immediately obey orders.

Before they were exported, the horses were brought in from the range and without any handling whatsoever, they were herded the many miles toward the ships continually picking up new horses as they went.

Once at the harbor, the horses were herded into a ship's hull. They were packed as tightly as possible. Then the grueling experience began. When there were no complications the ocean journey took about a week. During this time, they received very little if any food and water. The seas were generally rough and since horses can not throw up seasickness was very dangerous for them.

Once the reached their destination buyers were waiting on the dock to choose one.

As a boy, my father lived--in an apartment above the family business--on the quay of one of Denmark's major ports. He told me of regularly standing in a window and looking down at the spectacle below.

He said that once a horse had been bought, a battle would incur. The emaciated animal--who had never seen anything other than the Icelandic countryside before--would be forcible hitched to a cart. Then the new owner would jump into the car and whip the frightened horse up the steep cobble clad street leading to the city and from there on home. By the time the horse reached the farm, he was considered broken in.

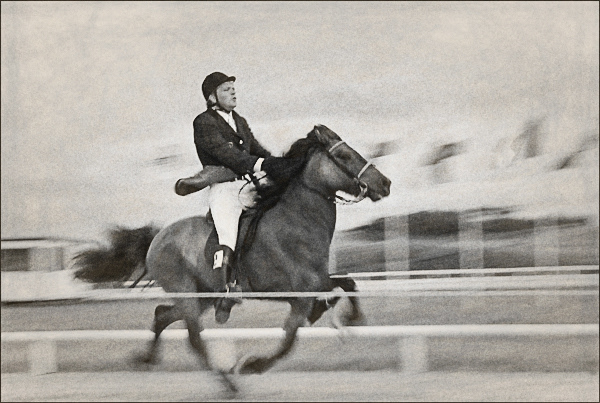

In Iceland, like everywhere else, the time came when mechanization took over the role of brawn from the horse. Whereas horses were still as popular a food source as ever, the exports to foreign countries stopped. Horsemanship dwindled. Less and less people rode and only the old timers remembered the old traditions. There were still some die hard horsemen, but now journeying on horses was only done for pleasure by people who had other jobs.

This sad state of events went on for some time, but Iceland had always been a nation of riders and always will be. By and by the interest in horsemanship was reignited. Farmers began breeding horses solely for riding purposes rather than slaughter. Toelt was invented and became the favored gait. Riders still wanted powerful, energetic horses and looked for action rather than comfort in the horse's movement.

Horses were not supposed to stand still when you mounted them but should jump forward. If they remained standing during the process, the rider would kick them in the side with his toe to signal what was expected of them.

The European Icelandic Horse rage began in the nineteen sixties and spread like wild fire. Now the Icelandic Horse became exported as a riding horse rather than a stubborn work animal for poor farmers and everyone wanted one.

It all began with Gunnar Bjarnasonn. Like so many other young Icelanders, he studied at a Danish agricultural school. He met other breeds of horses and thought none could compare to the Icelandic Horse and envisioned an enormous popularity of them throughout the world.

By and by her became a government appointed ambassador for the Icelandic Horse. Then, he cooked up the idea of once again bringing a shipload of horses (mostly foals) from Iceland to Germany. This time they traveled in more comfort, and once again buyers were waiting on the quay for them. Gunnar had made good use of the recent volcanic outbreaks in Iceland and he had received great newspaper coverage about how all the horses affected by them would be slaughtered unless they found new homes in Germany.

Loads of people wanted to save one of the cute babies and they were all bought in a flash.

He conveniently forgot to tell people of all the horses that were being slaughtered in Iceland all the time, but the important thing is that his ruse paid off.

People loved their new horses and the popularity of these delightful, dependable, easy keepers spread like wild fire--first in Germany, then in Denmark, Holland, Austria, and Norway. Everyone wanted an Icelandic Horse and before long hordes of Icelandic horse owners were toelting together through the forests at a fast clip. It was incredibly fun.

On that note, I am going to end my story of the history of the Icelandic horse. I want to dedicate a whole other section of the site to horse tradition in Iceland 50 years ago and the development of the European Icelandic Horse rage. It occurred to me, lately, that, soon, I may be one of the few people who left alive who were a part of that story--not just among people in the United States but even among those in Iceland as well.